The Tempest and Hamlet at the Globe

When that I was and a little tiny boy,

With hey, ho, the wind and the rain,

A foolish thing was but a toy,

For the rain it raineth every day.

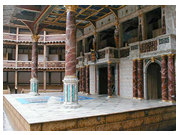

Performances are a marvel to behold from the yard at the recreated Globe theater—don't miss your chance to take a stand with the groundlings. The space is surprisingly intimate: 600 playgoers in the yard, perhaps twice that many in the galleries, yet it seems even smaller. Large, covered, and ornate, the stage projects into the crowd so far, that you feel yourself a part of the play. No proscenium arch protects you from involvement: you sense the space between bodies and follow their movement on stage as if you were standing among them—which indeed, you practically are. No need to shout ridicule or encouragement at the players to feel part of the performance: even standing mute, you can't help but be implicated—not just intellectually and emotionally, but physically, corporeally—in the action.

Don't buy groundling tickets alone, however. London weather is fickle at best; this being one of the coldest and wettest Mays on record, I and my fellow standees were drenched by a steadily increasing drizzle and several downpours during the final preview performance of The Tempest. Buy some insurance in the stands, if your pocketbook allows. Don't wait to try your luck in the returns line on performance day, as I and my companion did, along with several other penitent souls.

The experience of standing in the rain to watch such an appropriately named play—indeed, if the downpours had stopped after Act II, who would have complained?—does serve to connect you across centuries of lost time with the groundlings who stood near here, in a theater almost exactly like this, to witness the original performances of these plays, when their author still walked the earth and endured wind and weather like any other man. Suddenly the import of lines like those cited from the end of Twelfth Night at the beginning of this account—or paraphrased from it in the last sentence—is unmistakable, and provides welcome comic relief from one's own soggy plight. Shakespeare wrote such lines for you and your fellows, you now realize—all those brave groundlings down the years who've proved willing to stand out in the rain and risk drenching to catch the best view possible of his plays.

|

|

| Globe from the Thames | |

|

|

| View from Stage Left toward Galleries | |

|

|

| Globe's Stage |

The Tempest

Would it be too much to say that the perhaps best things about this particular production of The Tempest were such foul weather friends? Certainly Vanessa Redgrave's ad libbed "Let me not...dwell / In this rainy island by your spell" at the end was almost the best bit of an otherwise rather disappointing performance. How she could agree to take on perhaps the plum, and certainly the most self-referential, of all Shakespeare's roles—a true valedictory for thespians in late career, and the kickoff role for the millennium Globe season—and not manage to do more with it is a mystery in itself. We were expecting a tour de force; what we got was an actress on holiday.

My first recollection is of her bungling the manage of her magic staff—a long walking stick of an affair that she was supposed to twirl Ninja-like in token of Prospero's power, but instead nearly lost control of and dropped in her lassitude. Worse was the weird, vaguely Scottist accent she affected throughout—flat, gritty, ungenerous, a style of speech without music, incapable of stirring an emotional response in the audience. Glynne Wickham as I recall was an early supporter of the Globe reconstruction; my former scholarly self was distracted by the idea that perhaps Redgrave was directed to "seem Scottish," in a mistaken effort to suggest that Prospero should be construed as a complimentary personation of James I, whose "marriage" England and Scotland under his paternal reign found expression in masques like the one presented later in the play. But on second thought, I can't imagine my suspicions were right. So Redgrave's strange turn as a dour Scot can only remain one of the unexplained mysteries of theatrical history.

Ariel in this production was similarly affectless, but to much greater effect. Rather than the anxious puppydog he's usually portrayed as being, he became a kind of saintly schizophrenic presiding over the play, toying with these mortals in almost scientific detachment, bemused by their responses, capable of killing heartlessly if his master's voice should tell him so, but thankfully spared that role by Prospero's own good intentions.

What of Miranda? Oh, she was more than adequate, indeed appealingly naive, from the moment we first see her carrying a stuffed unicorn doll—well, okay, a little precious—to the last, when the even sillier director couldn't resist the joke of having her seem a bit over-interested in some of the other men (besides Ferdinand) she finds in this brave new world of hers: first Antonio (a nice joke at the beginning, but quickly a little queasy), and then the Captain—the only other actor of the same race, as I recall, in the production (a bad joke from the start).

As indicated above, the best bits here were the ones that made the audience a part of the performance. You should go to this Tempest not for the stars, but for these magic moments among the lesser mortals (and immortals) that truly break the frame of the theater—or would if this theater had such a frame. Much more effective than Redgrave's explicit ad lib, for example, was the implicit sharing of the audience in the entering Triculo's plight. The words the actor spoke, were spoken for us—and we all felt it:

Trinculo Here's neither bush nor shrub to bear off any weather at all, and another storm brewing: I hear it sing i' th' wind. Yond same black cloud, yond huge one, looks like a foul bombard that would shed his liquor. ...Alas, the storm is come again! My best way is to creep under his [Caliban's] gabardine: there is no other shelter hereabout. Misery acquaints a man with strange bedfellows. I will here shroud till the dregs of the storm be past.

Even at a distance of four centuries, it seemed clear that here was recreated in us one of the major pleasures this play—and many others in the Shakespeare canon, even some you might not at first suspect—offered the groundlings in its contemporary audience on foul weather days: numerous lines and much stage business that, while perfectly appropriate to the story and the action on stage, were yet directly applicable to the audience's own soggy state. Not a few of us would gladly have exchanged places with Trinculo for a piece of that gabardine; others were no doubt even then sheltering under a piece of a stranger's parka, making nearly as unexpected a new acquaintance as Trinculo himself.

As in most productions, Stephano, Trinculo, and Caliban all but stole the show in their initial acquaintance and rebellion. Caliban here in particular exceeded all expectations and just about convinced the audience to make one with the rebels through the sheer persuasion of his "'ban, 'ban, Ca-Caliban" tattoo just before intermission. The groundlings among whom I stood—or rather swayed in time to the music—were stirred to a near frenzy as the song went on, clapping, cheering, dancing, splashing: almost as drunk as football hooligans at game's end, spoiling for a fight. Wet as we were, few of us wanted it to end. If ever a production truly exhibited what even monarchs had to fear from the theater's potential to foment popular rebellion, this was the one. Caliban, you realized, is the natural leader of this troop—or would be, if here weren't convinced of his own inferiority from the start. Stephano's just his figurehead.

On the other hand, the masque of Ceres and Juno that crowns Act IV did so in spades in this production. Never before have I witnessed so perfectly jaunty and thrilling a recreation of what attending a court masque must have been like. Iris and Ceres enter excellently coifed and in splendid white gowns that make them seem much nobler than any of the bumpkins stranded on this isle—and then Juno descends from above, sporting a gown that drapes down from heaven to earth in the front, with an effect that's truly regal: on stage, size does matter I guess. All have the larger-than-life air of professional entertainers, stars of stage and screen—indeed, whatever seemed missing from Redgrave's performance, they supply.

And just as in a true court masque, they easily penetrate their on-stage audience and invite them to join the dance in the graceful "no excuses" fashion typical of professional entertainers, while the unusually polished and energetic antimasque of nymphs and reapers is winding down. Miranda in particular seems to be having just the right kind of fun—a bride on her wedding day dancing at full court, wooing new husband Ferdinand with an an excellent "come hither" movement the nymphs have taught her. Someone must have done their homework and made true love to their employment here: like Caliban's rabble rousing, this most courtly masque eclipses the rest of this production — in particular, Redgrave's dry Scotch rendition of the most famous "we are such stuff as dreams are made on" speech that follows—and makes you not only glad you came, but just plain glad you are alive and a part of the proceedings.

What the director's vision was for this production, even in retrospect I can hardly say. At least we were spared the serious colonial critique that became all-too-common in late 20th century productions, even while given the most persuasively performed Caliban in many a moon (perhaps because he wasn't made to bear such oppressive interpretive weight). What I come away with is a renewed conviction of the impressive power inherent in two diverse kinds of theatrical spectacle: the rabble-rousing cheerleading that Caliban led us in at the end of the first half, and the more civilized, polished and professional, yet equally energizing masquing we witnessed in the second. Both depend on the unique space that's been recreated so meticulously at today's reconstructed Globe. We can only imagine that productions in the original must have held very similar thrills for audiences, even for those incapable—like those in charge of the current production—of taking home anything more substantial from the play.

Hamlet

It didn't rain for the evening performance of Hamlet I attended at least. And it seemed almost day under the floodlights, which fall equally on audience and stage, answering my fears that the nighttime Globe experience would seem less authentic. The artificial lights do obscure the sky, however, and partly disconnect you from the actual weather—so that Hamlet's "Do you see yonder cloud" line did not have quite the frame-breaking effect it otherwise might. His insult to groundlings in Act III did provoke raspberries, however—among them my own.

I wasn't expecting as much from this production, and didn't receive it. Mark Rylance, the Globe's artistic director, is apparently reprising a portrayal that made a name for him a decade or so back. He plays Hamlet as if he's seriously off his rocker from the start, and in such an annoyingly adolescent vein that one almost wishes Claudius would succeed in offing him. Rylance delivers his first several hundred lines (or so it seemed) with his back faced firmly towards the audience—a trick that may have worked on a proscenium stage, but which here makes one wonder why he's favoring those seated overhead in the back so much.

Claudius comes across like an English William Shatner, and seems fully as capable a ruler as a Danish Captain Kirk. Gertrude looks her age and comes across as an energetic if shallow society matron, allowing this production to completely avoid the Oedipal issues so often overplayed here.

The climactic swordfight between Laertes and Hamlet was the high point of the evening. Otherwise, Rylance's performance is just too mannered for the audience to derive much from the experience.

Exhibit Centre

The Globe Exhibit Centre is well worth the visit. There are fine, highly informative interactive exhibits—some unfortunately obscured by maps etched on the glass in front of them that become too visible when interaction turns the lights on. But why give pride of place at the end of an exhibit to a panel funded, and seemingly authored by, the anti-Stratfordians?

I wanted to use the sound booths that give you a chance to play out a scene with recorded actors, following prompts supplied on screen. They were monopolized by groups of visiting upperclass schoolchildren, however, boys and girls alike dressed in little suits and ties, who were apparently using them to record insulting and obscene speeches to share with their chums—a bad omen for the next generation of Shakespeare audiences, I'm afraid.